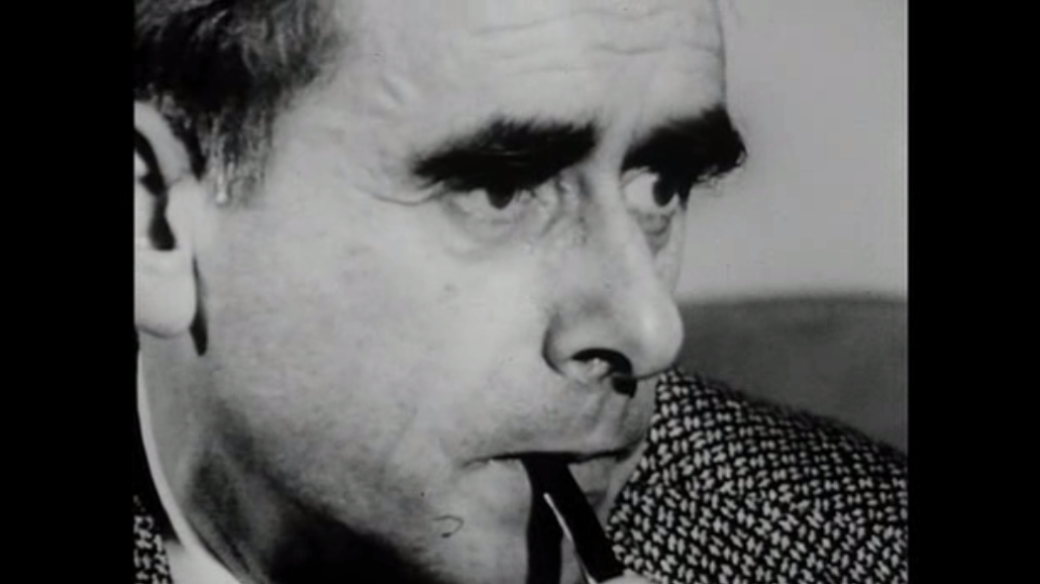

“You have to see your madness through. You have to take responsibility to the end… I believe there’s a job to do every day and from time to time, ideas do or don’t come. It’s like a seed you plant in the earth. Every day, you water it and whatever grows will grow. And there’s no point pulling the stem to make it grow faster. If you do, you uproot it and that’s that!” – – – Henri-Georges Clouzot

L’enfer d’Henri-Georges Clouzot (Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno) is the apt title for a piece of abstract art, “kinetic art” as the French film-maker himself would have claimed. A 2009 documentary depicting the reels and reels of film left behind, and the story that goes with it, of what is unquestionably tagged the greatest film never made.

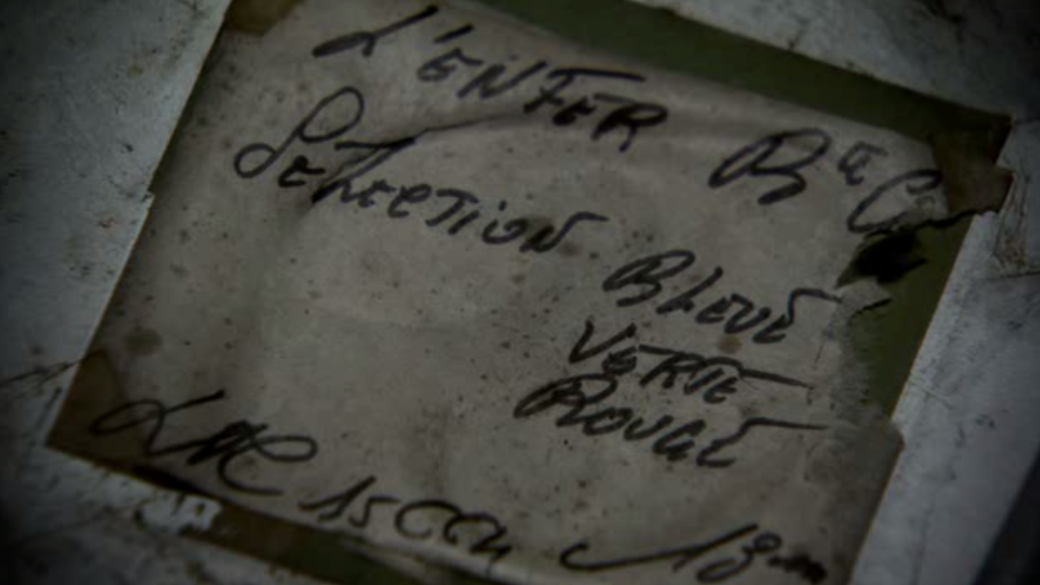

Assembled by Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea, they happened upon Clouzot’s widow Inès, from there it was apparent there was a regretfully unfinished film Inferno, from 1964, which the director believed was his most essential work – and nobody would ever see it. The documentary tells of how this enigmatic non-event warrants the fame and place in cinemas prestigious history. 185 cans of film, consisting of 13 hours of shot, exposed film. No sound, just images.

With renowned, established greats behind him, L’assassin, Le Corbeau, Quai des Orfèvres, Le salaire de la peur, Les Diaboliques, La Vérité, Clouzot openly suffered from insomnia, with a bout of depression in his history, when started to creative a story that gave physical, visual presence of anxiety and neurosis. Inferno became the obsessive perspective of Marcel, pathologically jealous of his new wife Odette. The script opened with the happy couple but would waste little time in rocking the stability of this fresh relationship.

Following Le mystère Picasso, Clouzot saw a different art form he could be passionate about, and this new wave of creative thinking would aid the development of his new project. Clouzot’s ambitious vision would certainly show in the endless footage of Inferno, so much of which makes it to this illustrious documentary. Unseen rushes of Clouzot and Romy Schneider meeting, hanging out like college kids. Schneider, at 26, was considered a big deal then, not quite 10 years after Sissi in 1955 – the making of her – it was rumored the part of the desirable Odette was written with Schneider in mind.

Marcel’s obsessive jealousy was magnified through such a dynamic use of color, camera framing, dazzling motion tricks, roaming lighting, I mean this is the kind of technical achievements that still knocks you out of your seat today. Inferno was to be a black and white film crammed with a kaleidoscope of emotion-fueled colors. Visions and fantasies, vivid and intoxicating, explode with disorientating colors and light, women appear to wear blue lipstick, the lake inverts to a rich red, . But also, the incomparably radiant Romy Schneider dominates much of the fallacy sequences, revolving glares reveal and hide the contours of her face, glowing tones, the character of Odette licks a front-of-lens water-fall, snippets of arousing caresses, oil-covered flesh, reverse motion of her smoking, plus an immaculately shot of a nude Schneider laying on a track as a train approaches. Words do not do any of this justice.

To state Inferno was a big budget production was only skimming the surface, not an epic film but rather an intricate, super-explorative attempt to feed Clouzot’s unrelenting cinematic eye. That he demanded so much in preparation and execution both emphasized he pure passion and determination, but also shining a light on the difficult working conditions, cast and crew wore down by re-shoots, days and days of shooting, meticulous construction.

Was Clouzot himself obsessive and pathological, like the character of Marcel? Turns out, actor Serge Reggiani (who played Marcel) left the film late into the shoot – he and Clouzot locked horns and only served to build the tension. Clouzot later suffered a heart attack while on location, Schneider herself summarized that this was a turning point that needed to happen to sadly halt the project, his unfinished symphony.

Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea demonstrate a real, raw pride here in bringing as much of this forgotten dream back to life – clearly they are fans of Clouzot. Accompanying the delicious archive footage of Henri-Georges Clouzot, Romy Schneider and co, the documentarians employ Bérénice Bejo (as Odette) and Jacques Gamblin (Marcel) to read lines of dialogue from Clouzot’s rich, unraveling screenplay. A genius move, able to bring to the screen some of the naturalistic exchanges of pure paranoia. Various V.I.P. interviewees providing much of the first-hand accounts of Clouzot’s journey include Costa-Gavras, Jacques Douy, Inès Clouzot, while Janice Jonesusic’s editing pulls it all together, and Bruno Alexiu’s score fits the era and enigma perfectly.

L’enfer d’Henri-Georges Clouzot is an integral part of not just the history of cinema, but also a prestigious reflection on the modern movie. Documentaries continue to bang down the door, their significance is matched by their stimulation. The beautiful, bewildering, images of Romy Schneider is enough to compel, but the untold story of Clouzot’s Inferno has to be seen in all its glory – the film that was never to be seen by audiences proves to be both a tragedy and a victory for the art of film. A treasure to keep close to your cinematic heart for all time.

Recent Comments