There is a certain mystique that swirls around those charged with our safety and well-being. Cinema tapped into it as early as 1903 when a posse overtook the bandits in The Great Train Robbery, inspired by a robbery committed by Butch Cassidy, himself a film favorite for seventy –odd years.

That film set the pattern for the genre by incorporating two key elements: 1) that realism, achieved through camera angles, crisp editing and location shooting, is key to audience involvement, and 2) conflict is most effective if the story is based on an actual event, an occurrence or situation with which the audience may already be aware.

The Great Train Robbery was 12 minutes long and cost an estimated $150 to make, setting a trend for both economy and compactness that was generally followed into the Sixties when the shine on the badge began to tarnish and stories became more complex, characters on the side of the law more conflicted. By the time the Seventies kicked-in, “rogue” cops and undercover agents became staples, adding additional layers of suspense and wiping-out the “white hat / black hat” premise of the likes of High Noon. Cops were now portrayed with the same frailties and objectives as their targets that frequently came in the form of other cops.

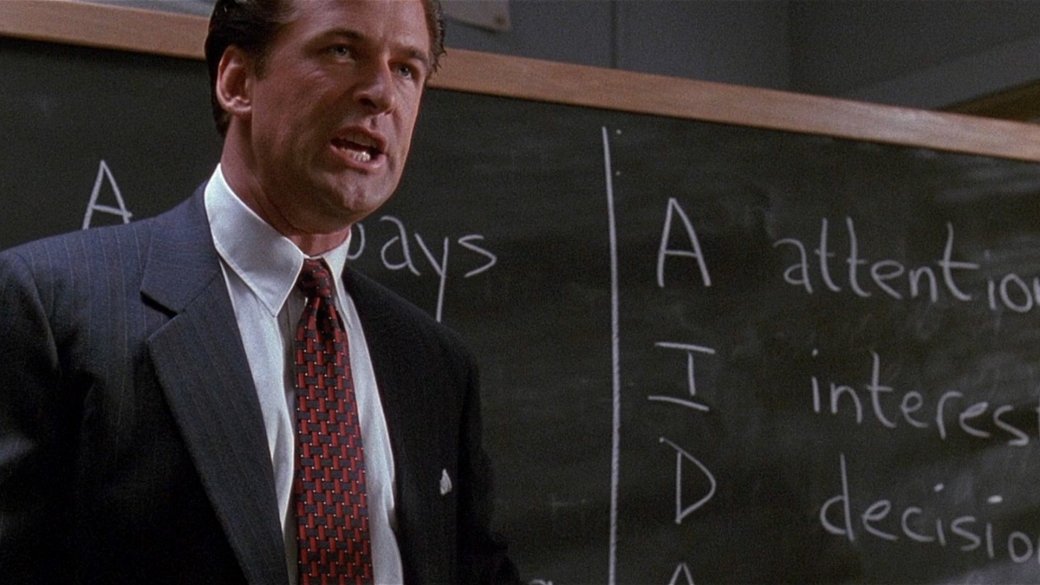

Whether it’s a frustrated and dedicated maverick taking on a situation alone – often against orders – or an escalated paramilitary effort launched due to the scale and sophistication of the lawbreakers, we like our law enforcement tales precise and no-nonsense. Despite the genre’s popularity and steady box office track record, only three films presented exclusively from the cops’ POV have been awarded Best Picture: (In the Heat of the Night (’67), The French Connection (’71) and The Departed (’06). The lead characters in each stepped outside the norm, for better or worse. Another, L.A. Confidential (’97) – probably the most acclaimed of the genre and one of only three films in history to win the “Big Four” critics’ awards – then, unfortunately, hit an iceberg on Oscar night.

Here are five others, chosen for their originality and long-term impact on the genre, that illustrate what’s best about the “boys – and girls – in blue”:

Bullitt Peter Yates (1968)

By the end of the Sixties, cops had gone from being the cavalry that saves the day to a much more questionable entity. Dirty cop scandals and the repeated aggressive behavior towards peacenik protesters threw plenty of shade on the profession, which is why Yates’ film was such an anomaly – and a huge box office hit. Steve McQueen, the king of cool himself, takes the lead as a cop facing down hit-men, politicians and public consternation while dutifully ensuring that a witness vital to a conviction is protected long enough to testify. It’s a clean and crisp, straight-forward story of little chatter or proselytizing that’s mostly famous for one key element that changed filmmaking – the car chase. There have always been chases in movies, but Yates know that a good car chase is like good sex – a little foreplay goes a long way. He takes his time setting it up, plays a bit of cat and mouse with the characters and the audience to get them involved, then…BAM! A camera bolted to the dashboard takes us on a hair-raising, stomach-flipping high speed chase over the hills of San Francisco. Audiences squealed, having never seen anything like it, and it still impresses today. The film is also notable because McQueen’s character, in spite of all the violence around him, only uses his weapon once, as a last resort. Damn fine, no-nonsense storytelling.

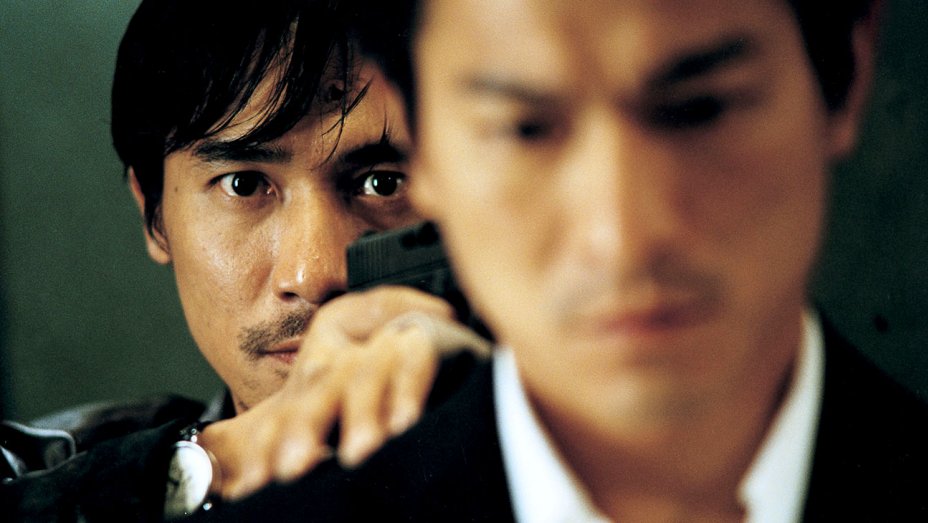

Infernal Affairs Andrew Lau/Alan Muk (2002)

Moles and double-dealing are rife in this tale of Hong Kong Police infiltrating a deadly triad while, at the same time, the said triad deploys a similar strategy against the force. The suspense resulting from such a situation is elevated to greater heights by focusing the story on the two characters tasked with living double lives, constantly on the edge of discovery. Martin Scorsese basically remade the same story with considerable success in The Departed, but, while Lau’s film is less glossy, it is more powerful in its impact, giving rise to a successful sequel and prequel. The plot is thick but involving as lines between good and bad blur to the point of invisibility by the time things untangle – sort of – at the end. The film was both a huge critical and box office success, spawning a video game and a television series, as well as remakes in Korea, Japan and India (and the aforesaid USA/Scorsese film). This is a milestone of the genre.

Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad) José Padilha (2007)

Padilha directs this tale of the Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais (BOPE) and the daunting task of dealing with crime in the sprawling, impenetrable favelas of Rio de Janeiro. City of God screenwriter Bráulio Mantovani penned the script and the film was a cultural phenomenon in Brazil, only to be outdone by a sequel three years later. Although the film was a domestic commercial success and won the Golden Bear at the 2008 Berlin Film Festival, foreign critics – especially North American – were appalled by the portrayal of brutal paramilitary law enforcement and questioned the film’s moral compass. A decade later, however, we see the similar domestic SWAT forces maintaining control the streets in cities from Paris to St Louis. Amidst the considerable action sequences we witness relationships on both sides of the battle lines – and sometimes across those lines – all the way to the bitter and controversial ending.

Fargo Joel Coen (1996)

If ever there was a “good cop”, it’s Captain Marge Gunderson. Despite being seven months pregnant and battling morning sickness, we quickly learn that she is the brains of the Brainerd Police Department, someone with a clear vision of right and wrong, tough but respectful, and altogether fearless. This is probably Frances McDormand’s signature role to date – funny, compassionate, understanding…and relentless. She’s matched with two cretinous, “kinda funny lookin’” but deadly kidnappers (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) who hired by car dealer and milquetoast loser, Jerry Lundegaard (William H Macy) who is looking for a shortcut to success – in all the wrong places. All the stars aligned for the Coens on this venture. The bizarre story of (mostly) true events and the chilly Paul Bunyanesque setting entices them with enough material to provide us with a virtual salad bar of quirkiness. Every scene is pitch perfect, beautifully executed and never what you would expect – a tough act to pull off, but one the Coens make look effortless. I vaguely remember Roger Ebert, in his televised review, saying that films like Fargo are the reason he loves movies, and I have to agree. It’s hard to remain fresh and to present something so original in such a staid and established genre like police drama.

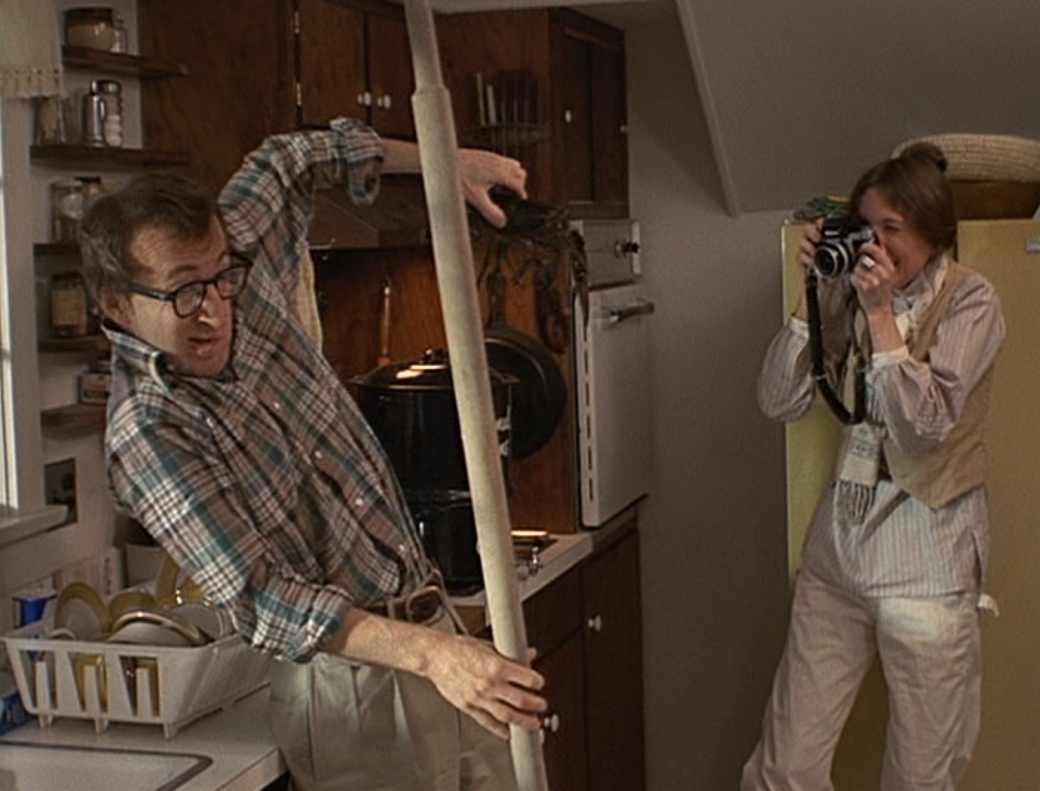

Witness Peter Weir (1985)

Despite having only directed 18 features, Aussie Peter Weir has an insanely eclectic and award-laden filmography that covers the mysterious disappearance of schoolgirls on a picnic (Picnic at Hanging Rock) and a man who loses his strawberry allergy in a plane crash (Fearless) to a young guy adopted and raised within a TV show (The Truman Show) and a father/husband who moves his family into the Central American jungle, only to lose his mind (Mosquito Coast). He can also brag to the fact that he has never made a bad film, and his drama about a detective protecting a young Amish boy who was eyewitness to a murder is one of his best. It is also arguably Harrison Ford’s most proficient screen performance as John Book, the wounded detective who is entranced by the Amish community that shelters him. Weir shifts gears on us when we jump from urban grit to the secluded pastoral lifestyle, inviting us to fall in love with the simplicity as well – and we do. Book’s integration into the community culminates in a community barn-raising that is as organically inspirational as anything on film, making events that follow when the “real” world invades the story afterward all the more unsettling. Unfortunately, Weir hasn’t made a feature for the past seven years and cinema misses his humanity. Perhaps, like John Book, he has found that idyllic place far away from the dirty daily shuffle?

Those are five of my essential police dramas where being responsible for the public safety leaves one open to all forms of temptation and invites both criticism and admiration, making this genre one of the most durable.

Recent Comments